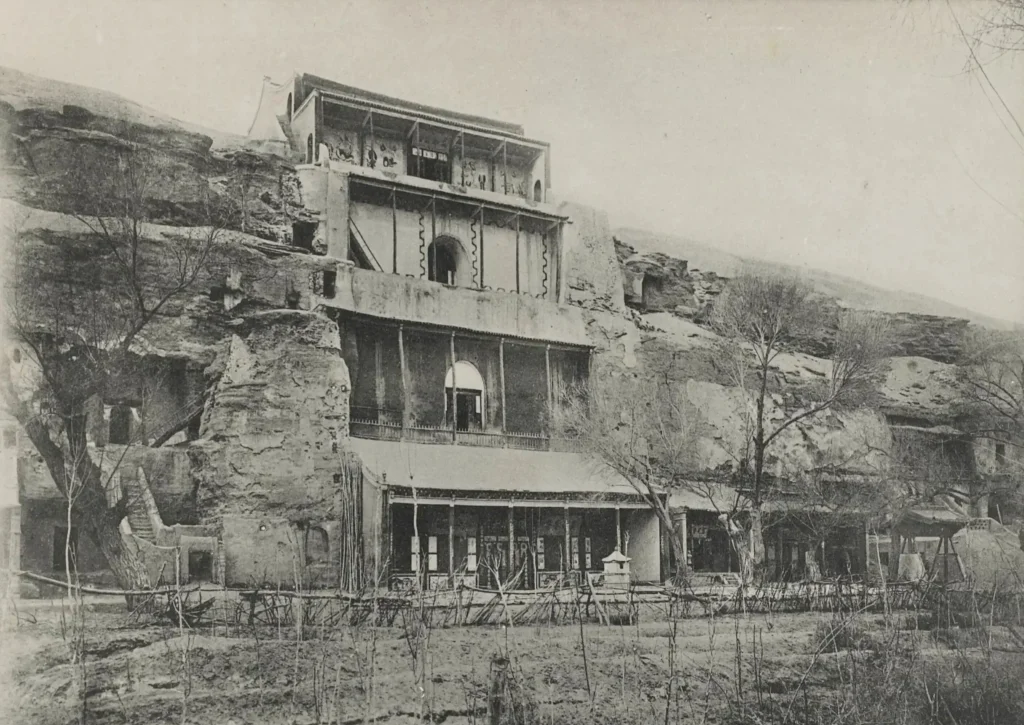

The Mogao Caves are located in Dunhuang, at the western end of the Hexi Corridor. Their excavation spanned approximately 1,000 years, from the Sixteen Kingdoms period to the Yuan Dynasty—a duration unparalleled among China’s cave temples.

They stand as both a dazzling artistic treasure trove of ancient Chinese civilization and a vital testament to the dialogue and exchange between diverse civilizations that once unfolded along the ancient Silk Road.

Historical Changes

During the Jin Dynasty, it was known as “Xianyan Temple.” In the Former Qin period of the Sixteen Kingdoms era, it was formally named “Mogao Grottoes.” In the late Sui and early Tang dynasties, it was called “Chongjiao Temple.” During the Yuan Dynasty, it was known as “Huangqing Temple,” and in the late Qing Dynasty, it was referred to as “Leiyin Temple.” However, these names were all temporary designations used for a short period to represent the entire Mogao Grottoes complex.

Regarding the founding date of the Mogao Caves:

1. According to the late Tang ink inscription “Record of the Mogao Caves” on the north wall of the front chamber of Cave 156, the caves were first constructed during the late Western Jin Dynasty;

2. Additionally, P.2691 “Geographical Records of Shazhou” states that the caves began construction in the ninth year of the Yonghe era (353) of the Eastern Jin Dynasty;

3. Furthermore, the Stele Inscription of Mr. Li’s Restoration of the Mogao Grottoes’ Buddhist Niches, dated to the first year of the Shengli era (698) of the Wu Zhou dynasty and housed in the Dunhuang Research Academy, records that the monk Yue Zun began excavating the first cave in the second year of the Jianyuan era (366) of the Former Qin dynasty.

Currently, all three accounts coexist, but the 366 CE date is most commonly accepted. Following the Former Qin dynasty, the caves underwent construction across eleven successive eras: Northern Liang, Northern Wei, Western Wei, Northern Zhou, Sui, Tang (divided into early, peak, middle, and late periods), Five Dynasties, Song, Uyghur, Western Xia, and Yuan. Spanning a millennium, by the Wu Zhou period (early Tang dynasty), there were already “over a thousand cave chambers.”

Regarding the founding date of the Mogao Caves:

1. According to the late Tang ink inscription “Record of the Mogao Caves” on the north wall of the front chamber of Cave 156, the caves were first constructed during the late Western Jin Dynasty;

2. Additionally, P.2691 “Geographical Records of Shazhou” states that the caves began construction in the ninth year of the Yonghe era (353) of the Eastern Jin Dynasty;

3. Furthermore, the Stele Inscription of Mr. Li’s Restoration of the Mogao Grottoes’ Buddhist Niches, dated to the first year of the Shengli era (698) of the Wu Zhou dynasty and housed in the Dunhuang Research Academy, records that the monk Yue Zun began excavating the first cave in the second year of the Jianyuan era (366) of the Former Qin dynasty.

Currently, all three accounts coexist, but the 366 CE date is most commonly accepted. Following the Former Qin dynasty, the caves underwent construction across eleven successive eras: Northern Liang, Northern Wei, Western Wei, Northern Zhou, Sui, Tang (divided into early, peak, middle, and late periods), Five Dynasties, Song, Uyghur, Western Xia, and Yuan. Spanning a millennium, by the Wu Zhou period (early Tang dynasty), there were already “over a thousand cave chambers.”

Overview

Status

The Mogao Caves currently comprise 735 caves, preserving over 45,000 square meters of murals, more than 2,400 colored sculptures, and five Tang and Song dynasty wooden cave eaves. They stand as a microcosm of the development and evolution of Chinese cave art, holding a revered historical status within the field.

Culture

The Mogao Grottoes stretch over 1,600 meters in length, divided into northern and southern zones. Currently, 492 caves contain preserved murals and sculptures, with the vast majority located in the southern zone.

In the northern zone of Mogao, only a few caves retain murals, while the rest comprise over 250 empty caves. The 492 numbered caves collectively contain over 45,000 square meters of murals, more than 3,000 colored sculptures, and five Tang and Song dynasty wooden cave eaves.

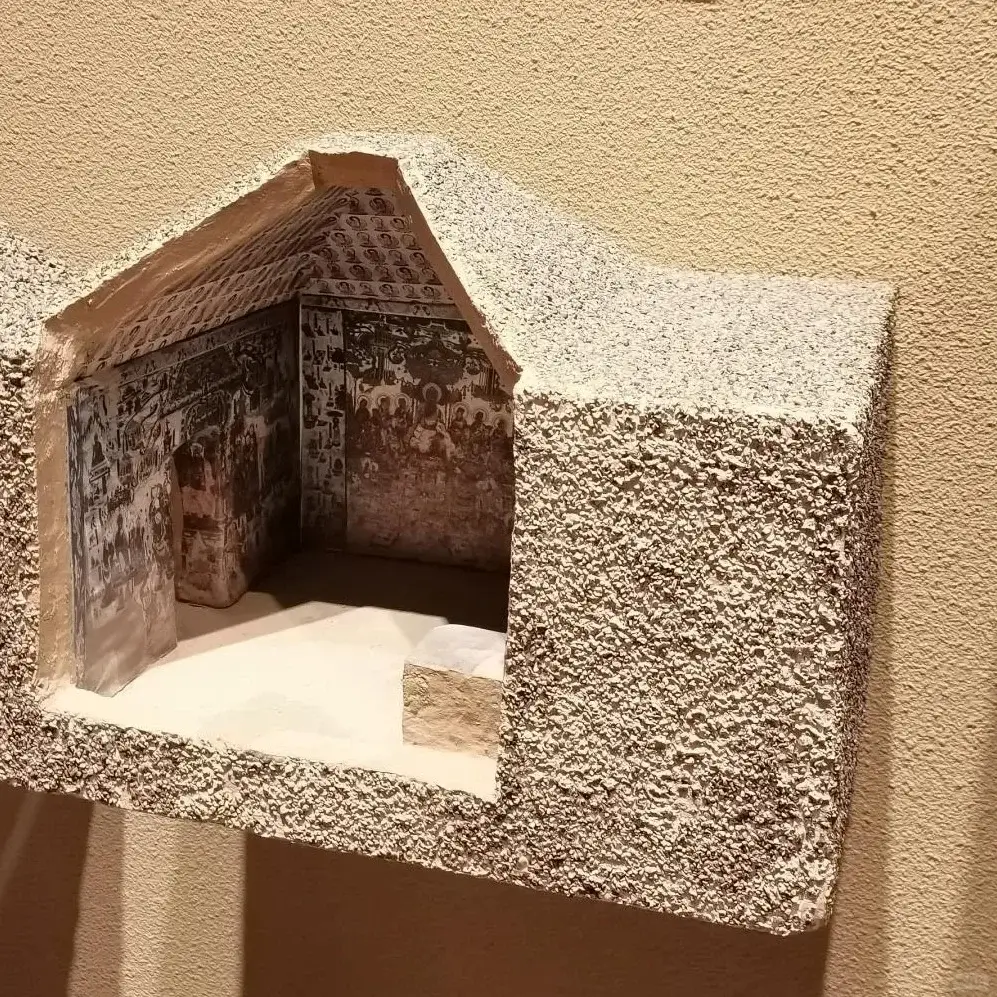

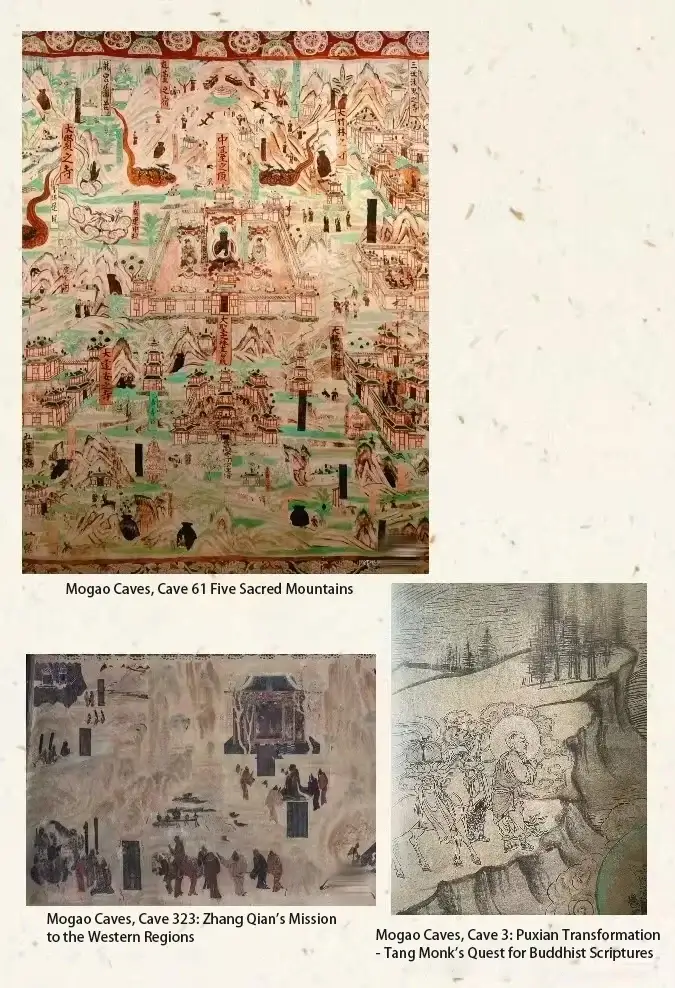

The tallest colored sculpture stands at 35.5 meters (the “Great Northern Figure” in Cave 96, built during the Zhengsheng era of the Wu Zhou dynasty), while the largest mural spans approximately 47 square meters (the “Mount Wutai Painting” in Cave 61 from the Five Dynasties period)

The caves primarily feature colored sculptures, with painted murals adorning all four walls and ceilings. The floors are inlaid with floral tiles, while exterior structures include cave eaves (or halls) and walkways. The interconnected caves form a unified Buddhist cultural complex integrating cave architecture, colored sculptures, and murals.

The Mogao Caves currently comprise 735 caves, preserving over 45,000 square meters of murals, more than 2,400 colored sculptures, and five Tang and Song dynasty wooden cave eaves. They stand as a microcosm of the development and evolution of Chinese cave art, holding a revered historical status within the field.

Culture

The Mogao Grottoes stretch over 1,600 meters in length, divided into northern and southern zones. Currently, 492 caves contain preserved murals and sculptures, with the vast majority located in the southern zone.

In the northern zone of Mogao, only a few caves retain murals, while the rest comprise over 250 empty caves. The 492 numbered caves collectively contain over 45,000 square meters of murals, more than 3,000 colored sculptures, and five Tang and Song dynasty wooden cave eaves.

The tallest colored sculpture stands at 35.5 meters (the “Great Northern Figure” in Cave 96, built during the Zhengsheng era of the Wu Zhou dynasty), while the largest mural spans approximately 47 square meters (the “Mount Wutai Painting” in Cave 61 from the Five Dynasties period)

The caves primarily feature colored sculptures, with painted murals adorning all four walls and ceilings. The floors are inlaid with floral tiles, while exterior structures include cave eaves (or halls) and walkways. The interconnected caves form a unified Buddhist cultural complex integrating cave architecture, colored sculptures, and murals.

Content

From an architectural perspective, the Dunhuang Caves primarily feature the following types:

Zen Cave

Characteristics: Compact space, intended solely for seated meditation practice.

hese are caves used by monks for seated meditation practice.

This form originated from India’s Vihara caves. Carved relatively early, they primarily appeared during the Sixteen Kingdoms and Northern Dynasties periods, with Cave 268 of the Northern Liang and Cave 285 of the Western Wei serving as representative examples.

Characteristics: Compact space, intended solely for seated meditation practice.

hese are caves used by monks for seated meditation practice.

This form originated from India’s Vihara caves. Carved relatively early, they primarily appeared during the Sixteen Kingdoms and Northern Dynasties periods, with Cave 268 of the Northern Liang and Cave 285 of the Western Wei serving as representative examples.

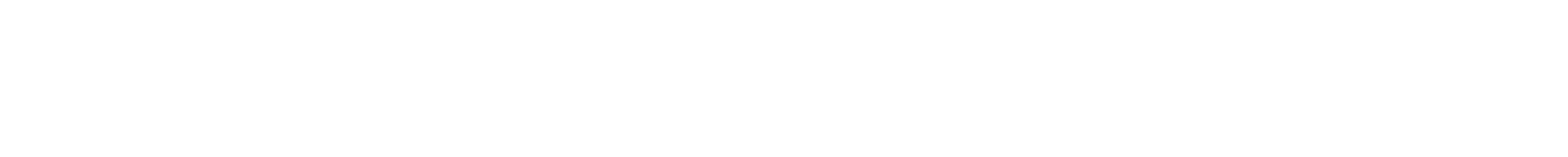

Central Pillar Cave

Features: A vertical stone pillar stands in the cave, with Buddha figures carved on all four sides. Devotees circumambulate the pillar in worship.

Originating in India, stupa caves feature a central stupa within the cave. Upon entering, devotees circumambulate the stupa clockwise in worship.

The stupa-temple caves of Dunhuang differ slightly from their Indian counterparts. They feature a rectangular floor plan with a square pillar at the rear extending straight to the cave ceiling, known as the stupa pillar. This pillar, modeled after the form of a Buddhist stupa, has niches carved on all four sides, each housing a Buddha statue.

The rear half of the ceiling in the central pillar cave is flat, while the front half features a gabled roof. The gabled roof refers to the traditional Chinese architectural form of a gabled roof structure.

Hall Cave

Characteristics: Square space with a niche for enshrining a Buddha on the main wall, resembling the layout of a wooden Buddhist hall.

These are the most numerous caves in the Dunhuang grottoes, typically square in plan with a large niche carved into the main wall.

These caves possess spacious interiors resembling halls, hence the name “hall caves.” Their inverted pyramid-shaped ceilings also earn them the designation “pyramid-roofed caves.” This pyramid form originates from ancient Chinese canopy structures, clearly reflecting the influence of traditional Chinese architecture.

After the late Tang and Five Dynasties periods, hall-style caves often omitted the central niche. Instead, a central Buddha altar was placed in the cave’s center, with statues placed upon it. Behind these statues, a screen extended all the way to the cave ceiling.

Great Giant Cave

Features: Giant Buddha statues over ten meters tall carved inside or outside the caves.

Giant Buddha statues are sculpted inside the caves, with corresponding temple structures in front of them. The main examples are Cave 96 (Northern Giant Statue) and Cave 130 (Southern Giant Statue).

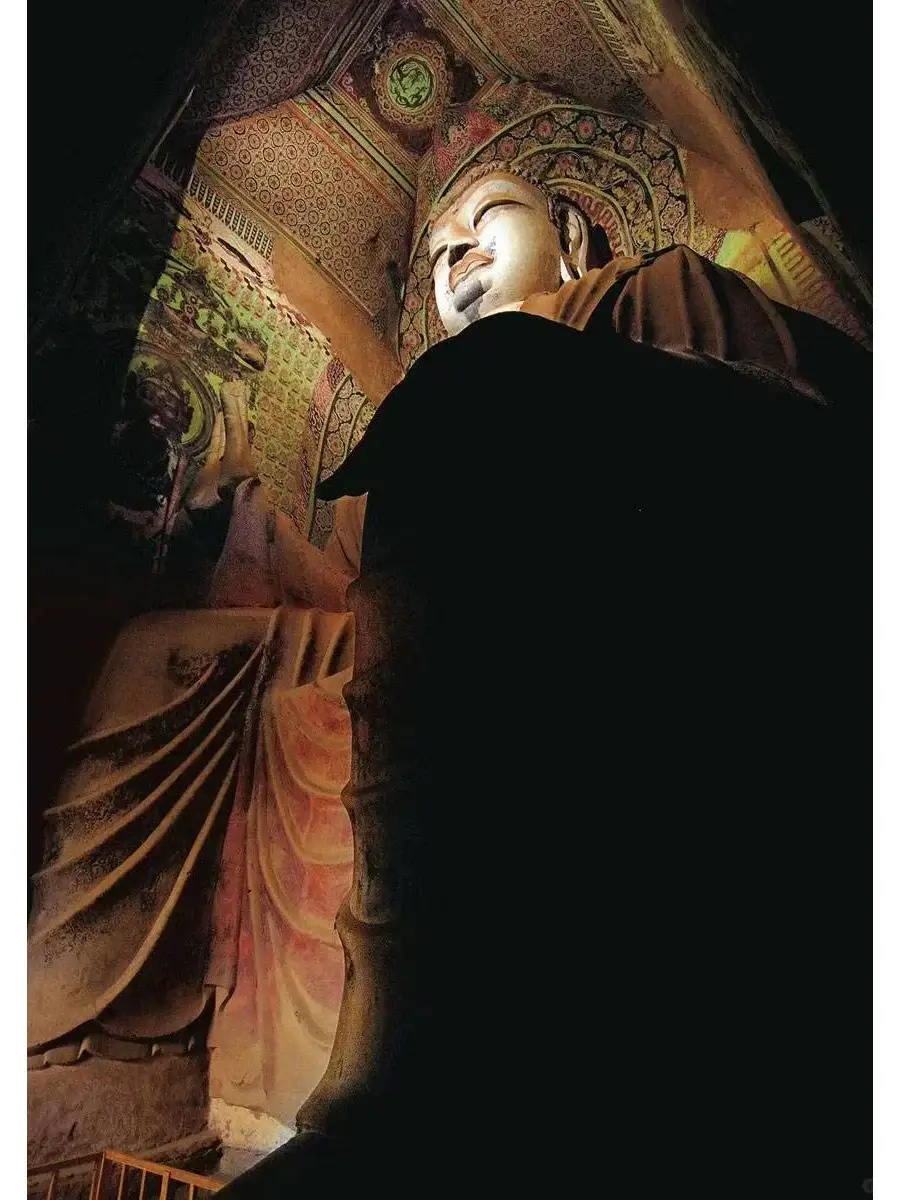

Nirvana Cave

Large nirvana statues were sculpted within the caves, with cave structures designed to accommodate the statues. The primary examples are Caves 148 and 158.

Monk’s Quarters Cave

The majority are concentrated in the northern section of the Mogao Caves. Fifty such caves remain today, serving as the living quarters for ancient monks.

These caves are relatively spacious and well-lit, featuring living facilities such as stoves and heated beds.

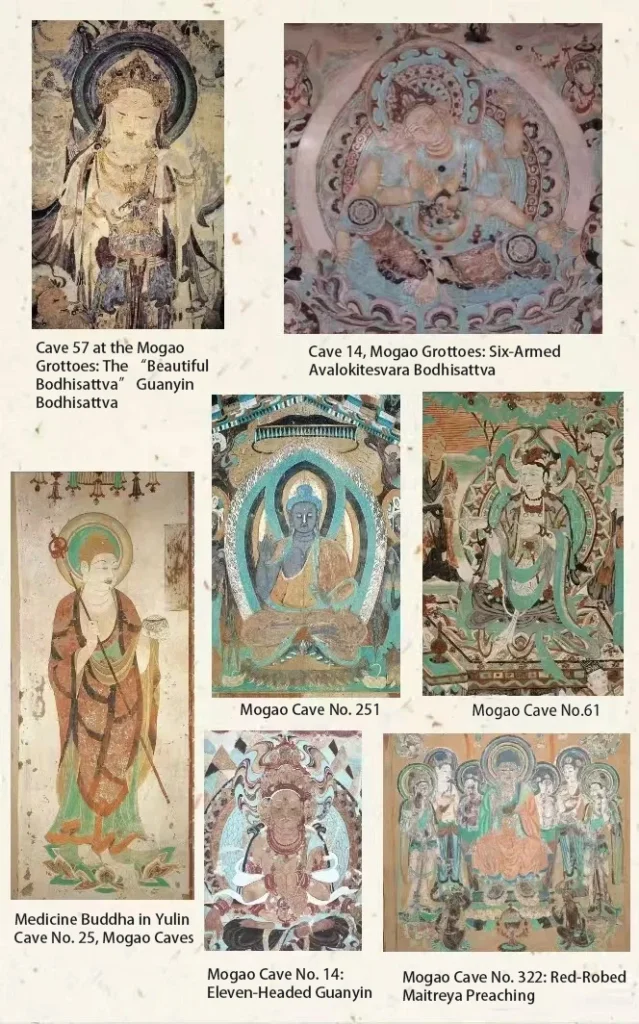

The murals of Dunhuang primarily feature seven categories of subjects:

Buddhist painting

The subjects depicted include the Buddha and his disciples, bodhisattvas, and celestial kings, who are objects of worship and always occupy prominent positions within the caves.

The subjects depicted include the Buddha and his disciples, bodhisattvas, and celestial kings, who are objects of worship and always occupy prominent positions within the caves.

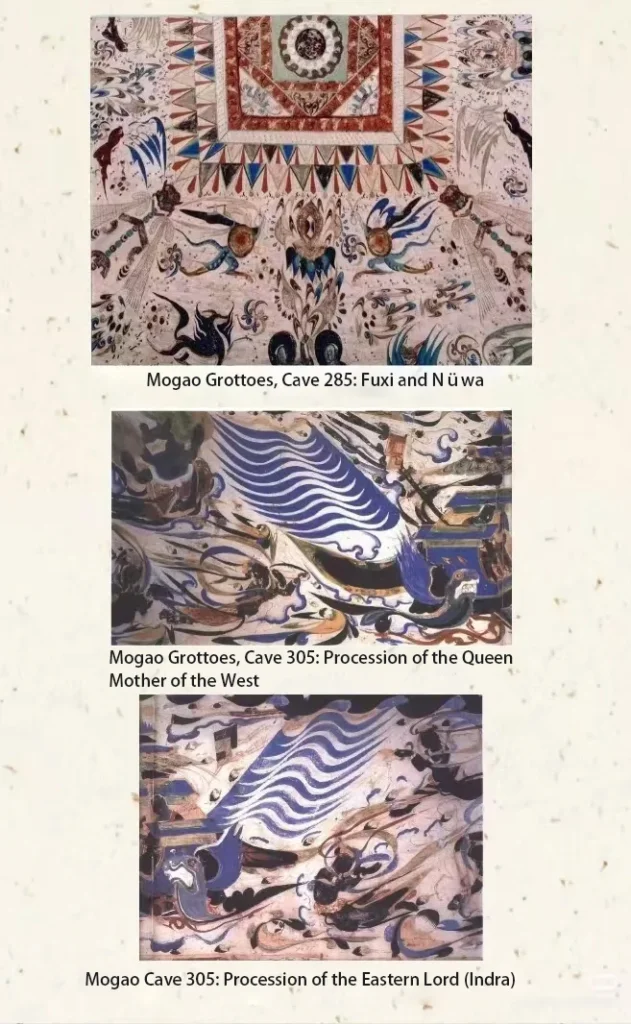

Based on Chinese traditional mythology

Depicting figures from traditional Chinese mythology such as the Eastern King, Western Queen Mother, Fuxi, and Nüwa.

The appearance of these figures in Buddhist caves indicates Buddhism’s growing acceptance of traditional Chinese culture, while also demonstrating how new forms of Buddhist art originating from the Central Plains began to influence the Mogao Caves.

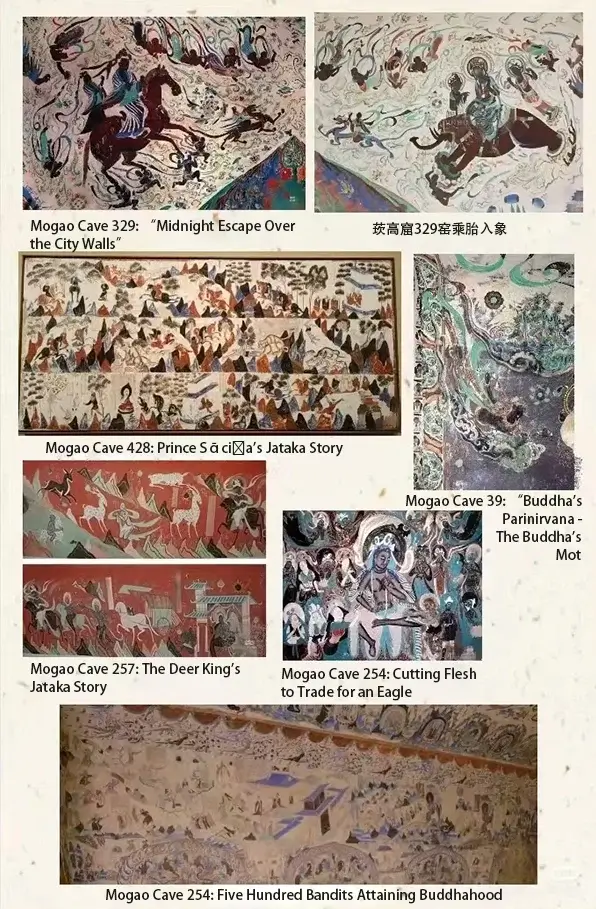

Buddhist Sutra Story Illustrations

Buddhist stories comprise three categories: Jataka tales, Buddha’s life stories, and karmic tales.

Jataka tales: Depicting the compassionate deeds of Shakyamuni Buddha in his previous lives as various animals, saving the world and benefiting sentient beings;

Buddha’s Life Stories: Biographical depictions of Shakyamuni Buddha’s present incarnation—from conception and birth through childhood, renunciation and asceticism, enlightenment, subduing demons, Buddhahood, and Nirvana;

Karma Stories: Narratives depicting Shakyamuni Buddha’s acts of guiding sentient beings toward liberation.

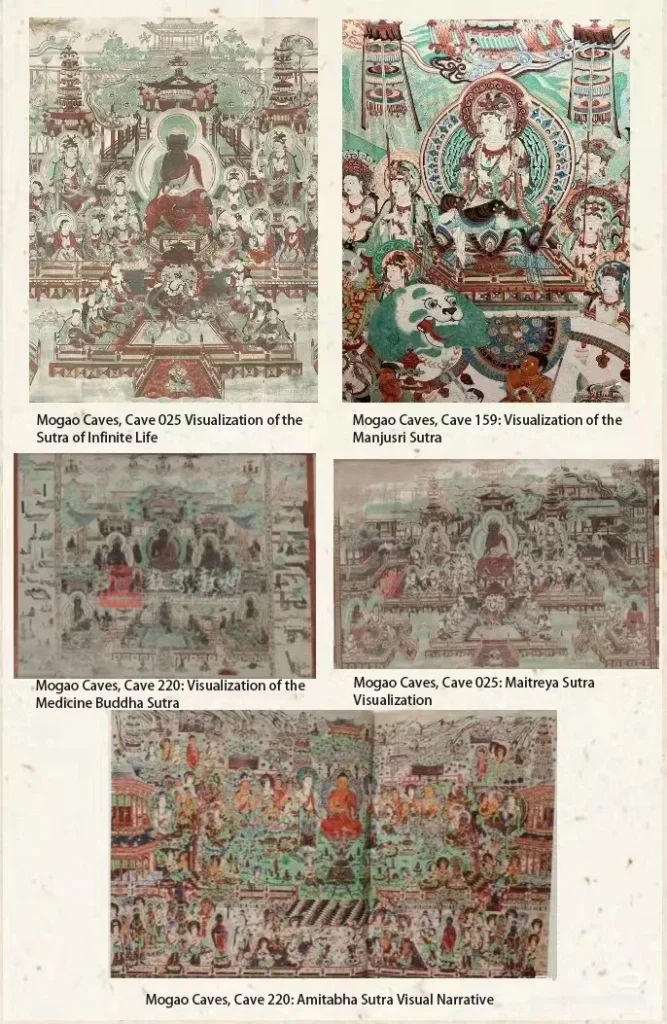

Transformation Painting

Sutra transformation paintings are large-scale works that comprehensively depict the main themes of Buddhist scriptures, featuring multiple scenes and expansive compositions. Unlike narrative Buddhist story paintings that focus on a single complete tale, these works synthesize various scenes recorded in the sutras.

Sutra transformation paintings became the primary subject matter of Dunhuang murals after the Tang Dynasty and represent quintessential Chinese Buddhist art. They embody the Chinese interpretation of Buddhism and reflect the aesthetic sensibilities of the Chinese people.

Buddhist Historical Sites Painting

Depicting stories from Buddhist history and legends. Since Buddhism spread from India to China, miraculous tales about eminent monks from both China and abroad have been widely circulated and frequently depicted in murals, providing crucial historical materials for studying the development of Buddhism.

Buddhist historical murals feature rich content, with notable examples including Zhang Qian’s mission to the Western Regions, the auspicious image of Liu Sake, and the Mount Wutai landscape.

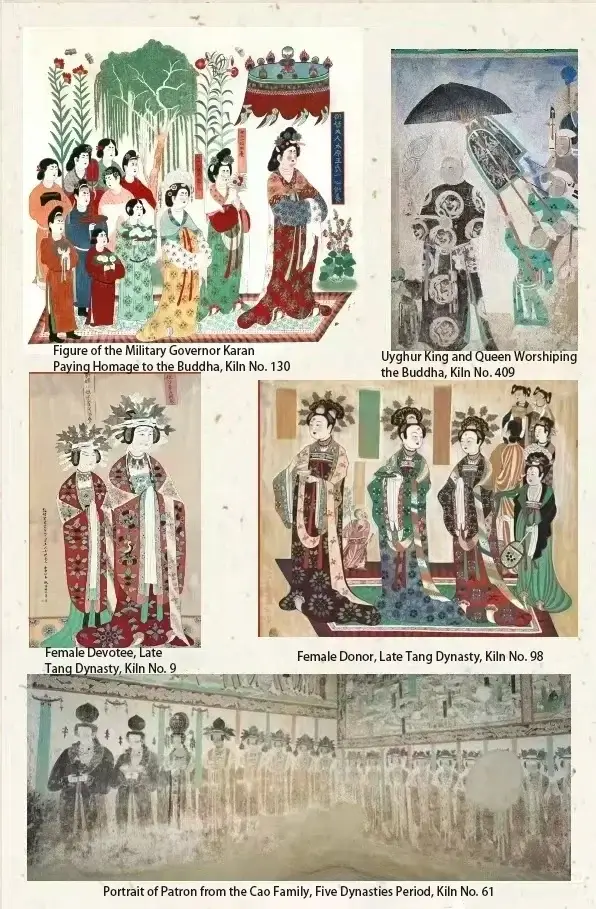

Portrait of the Patron

The patrons who funded the construction of the caves are known as donors.

Portraits of these donors not only reflect the appearance of people during the cave-building era but also serve as crucial materials for studying the figures, ethnic groups, clothing styles, and institutional systems of that period.

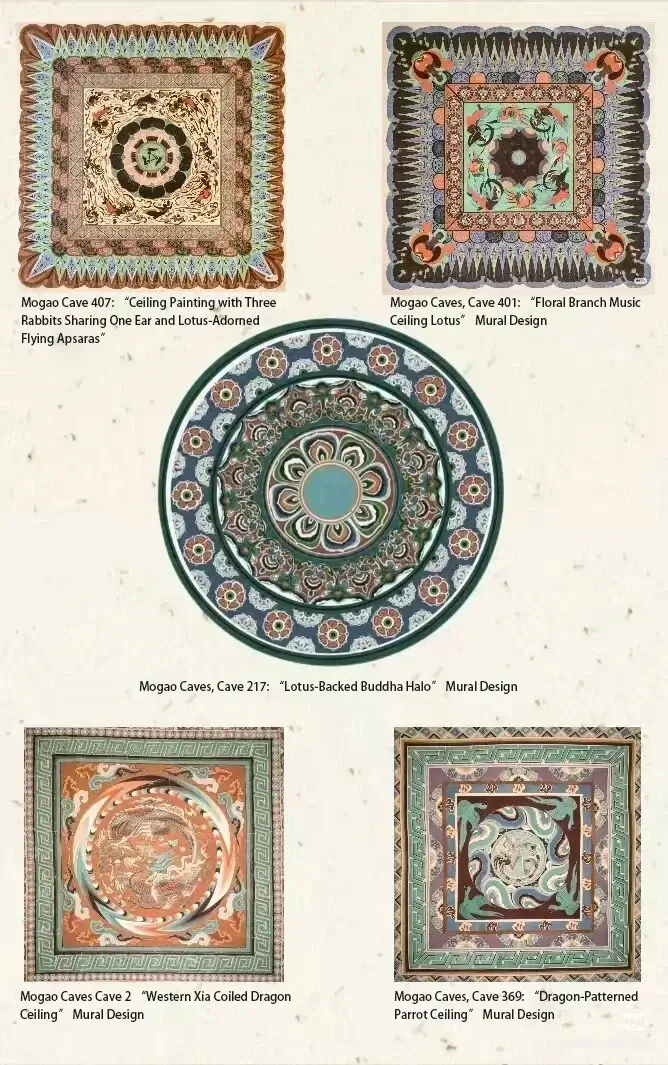

Decorative Pattern Painting

Patterns were painted on the cave ceiling, around the niches, and at the junctions of the walls, transforming the cave into a magnificent space. Decorative motifs from different eras reflect distinct styles of decorative art.

Value

Historical Value

The construction and historical development of the Dunhuang caves, the region’s long history, influential local clans and prominent families, as well as Dunhuang’s relations with surrounding ethnic groups and the Western Regions, have been scarcely or not at all documented in historical records.

The Dunhuang caves contain thousands upon thousands of portraits of patrons. These patron portraits and inscriptions vividly, richly, and authentically provide numerous historical contexts and clues. They reveal the historical events of prominent clans closely tied to Dunhuang’s history and the construction of its caves—clans such as Yin, Suo, Li, Zhai, Zhang, and Cao—and document their actual involvement in building the caves. These are invaluable materials for studying Dunhuang’s history during the rule of the Zhang and Cao Guiyi armies.

They also reveal the activities of various ethnic minority regimes in Dunhuang across different historical periods—including the Tuoba Xianbei, Tibetans, Tuyuhun, Uyghurs, and Dangmong—along with the intricate interethnic relationships and their cultural arts. These inscriptions reflect Tang dynasty ceremonial guard systems, slave systems, Tibetan administrative structures, and the regulatory practices of the Guiyi Army regime.

As the “throat” of the Silk Road, Dunhuang served as an indispensable transit point for foreign merchants and Han traders, functioning as both a hub for silk trade and a key transit location.

The construction and historical development of the Dunhuang caves, the region’s long history, influential local clans and prominent families, as well as Dunhuang’s relations with surrounding ethnic groups and the Western Regions, have been scarcely or not at all documented in historical records.

The Dunhuang caves contain thousands upon thousands of portraits of patrons. These patron portraits and inscriptions vividly, richly, and authentically provide numerous historical contexts and clues. They reveal the historical events of prominent clans closely tied to Dunhuang’s history and the construction of its caves—clans such as Yin, Suo, Li, Zhai, Zhang, and Cao—and document their actual involvement in building the caves. These are invaluable materials for studying Dunhuang’s history during the rule of the Zhang and Cao Guiyi armies.

They also reveal the activities of various ethnic minority regimes in Dunhuang across different historical periods—including the Tuoba Xianbei, Tibetans, Tuyuhun, Uyghurs, and Dangmong—along with the intricate interethnic relationships and their cultural arts. These inscriptions reflect Tang dynasty ceremonial guard systems, slave systems, Tibetan administrative structures, and the regulatory practices of the Guiyi Army regime.

As the “throat” of the Silk Road, Dunhuang served as an indispensable transit point for foreign merchants and Han traders, functioning as both a hub for silk trade and a key transit location.

Artistic value

The millennium-long construction of the Dunhuang Grottoes unfolded during a pivotal era in Chinese history—a period marked by prolonged division and secession following the Han dynasties, followed by ethnic integration and the unification of northern and southern China.

This pivotal era witnessed the Tang Dynasty’s zenith and subsequent decline. It marked the formation and evolution of Chinese artistic methodologies, schools, genres, and theories. Following the introduction of Buddhist art, China established and developed its own Buddhist doctrines and sects. Buddhist art became a vital category within Chinese artistic traditions, ultimately achieving its Sinicization.

The art of the Dunhuang caves, spanning a millennium, is rich in content and vast in quantity. Its artistic forms not only inherited the local Han and Jin dynasty traditions and absorbed the styles of Northern and Southern Dynasties and Tang-Song art schools, but also continuously accepted, adapted, and integrated artistic styles from India, Central Asia, and West Asia. It presents a history of Buddhist art and its gradual Sinicization process.

It also serves as a historical record of artistic exchange between China and the Western Regions. This holds significant importance for the study of both Chinese art history and global art history.

Scientific and Technological Value

The Life of Siddhartha, Buddha’s Life Stories, Maitreya Sutra Transformations, and Lotus Sutra Transformations feature numerous scenes of plowing and harvesting, depicting the sevenfold harvest.

These depict the agricultural landscape of the Dunhuang region spanning over 600 years from the Northern Zhou to the Western Xia dynasties, revealing the entire process of farming at the time: Farmers plow with one ox or two oxen yoked together (two oxen pulling a plow beam). Women sow seeds from baskets, wearing conical hats and wielding sickles. Farmers harvest ripe crops, while men thresh grain with flails. Men winnow using wooden forks and shovels, and women use winnowing baskets and sieves.

The murals also realistically depict various agricultural tools. In addition to those mentioned above, they include straight-shaft plows, curved-shaft plows, three-legged auger plows, iron plowshares, harrows, rakes, hoes, iron shovels, carrying poles, scales, hu (a unit of volume), dou (a unit of volume), and sheng (a unit of volume). Particularly noteworthy is the curved-shaft plow depicted in Cave 445’s Maitreya Sutra Transformation scene from the High Tang period. This plow, capable of adjusting plowing depth, provides us with the only precious pictorial evidence of the most advanced agricultural tools of that era.