Across the map of China stretches a towering, sturdy, and unbroken wall that spans the entire northern region from east to west—this is the Great Wall.

Historical Origins

The history of Great Wall construction dates back to the Western Zhou Dynasty. To defend against attacks by the Yan-Yun nomadic tribes from the north, the Zhou Dynasty built a series of fortified cities known as “Lieceng” for defense.

During the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, rival states vying for supremacy built Great Walls along their borders for mutual defense. The earliest structure was the “Chu Square City” in the 7th century BC. Subsequently, various feudal states—including Qi, Han, Wei, Zhao, Yan, Qin, and Zhongshan—erected their own “mutual defense Great Walls” for self-protection. After the Qin dynasty conquered the six states and unified China, Emperor Qin Shi Huang connected and repaired the Warring States-era walls, giving rise to the name “Great Wall of China.”

The Great Wall stands as the world’s longest and most extensive ancient defensive structure, spanning over 2,000 years of continuous construction since the Western Zhou period. Stretching across northern and central China, the total length is 21,196.18 kilometers, enough to span from the South Pole to the North Pole.

During the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, rival states vying for supremacy built Great Walls along their borders for mutual defense. The earliest structure was the “Chu Square City” in the 7th century BC. Subsequently, various feudal states—including Qi, Han, Wei, Zhao, Yan, Qin, and Zhongshan—erected their own “mutual defense Great Walls” for self-protection. After the Qin dynasty conquered the six states and unified China, Emperor Qin Shi Huang connected and repaired the Warring States-era walls, giving rise to the name “Great Wall of China.”

The Great Wall stands as the world’s longest and most extensive ancient defensive structure, spanning over 2,000 years of continuous construction since the Western Zhou period. Stretching across northern and central China, the total length is 21,196.18 kilometers, enough to span from the South Pole to the North Pole.

Since the reign of Emperor Qin Shi Huang, nearly every dynasty that ruled the Central Plains undertook the construction of the Great Wall. Over a dozen dynasties—including the Han, Jin, Northern Wei, Eastern Wei, Western Wei, Northern Qi, Northern Zhou, Sui, Tang, Song, Liao, Jin, Yuan, Ming, and Qing—all built sections of the Great Wall to varying degrees. From the perspective of the ruling ethnic groups, besides the Han Chinese, many minority ethnic groups that ruled China also built Great Walls.

During the Qing Dynasty, although large-scale construction ceased, sections were later built in isolated areas. It can be said that construction continued uninterrupted for over 2,000 years, from the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods through the Qing Dynasty.

During the Qing Dynasty, although large-scale construction ceased, sections were later built in isolated areas. It can be said that construction continued uninterrupted for over 2,000 years, from the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods through the Qing Dynasty.

Construction Process

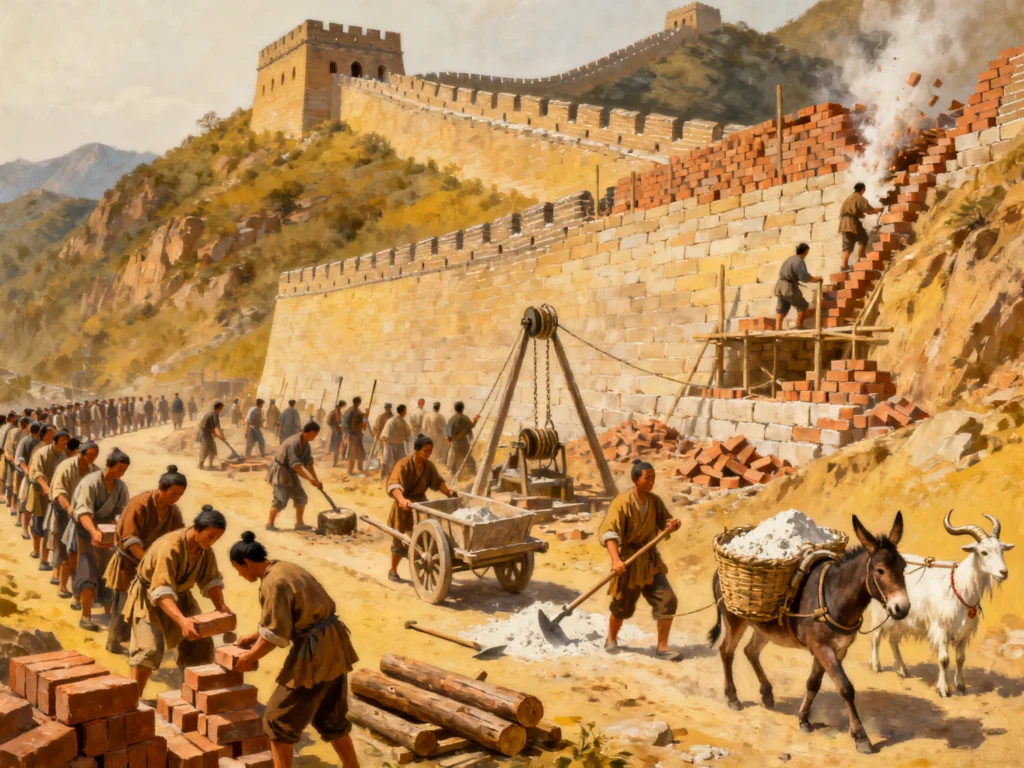

Utilizing the terrain and local materials, where mountains existed, steep ridges were employed whenever possible—steep and precipitous on the outer side, gently sloping on the inner side. Stones were quarried from the mountains, cut into uniform blocks, and filled with earth and lime, making them exceptionally sturdy.

In loess regions, rammed earth was the primary construction method. In desert areas, reeds and tamarisk branches were layered with sand and small pebbles. The Han Dynasty Great Wall near Yumen Pass exemplifies this technique. The preserved sections feature compacted sand and pebbles that resist erosion. In some areas, the sand and stones have bonded with the reeds, creating remarkably sturdy structures.

The staircases of watchtowers were constructed by layering dozens of strands of fiber. During the Ming Dynasty, key sections of the Great Wall were built with bricks and stones. Local kilns were established to fire bricks and tiles, while stone quarries were opened to produce lime.

In loess regions, rammed earth was the primary construction method. In desert areas, reeds and tamarisk branches were layered with sand and small pebbles. The Han Dynasty Great Wall near Yumen Pass exemplifies this technique. The preserved sections feature compacted sand and pebbles that resist erosion. In some areas, the sand and stones have bonded with the reeds, creating remarkably sturdy structures.

The staircases of watchtowers were constructed by layering dozens of strands of fiber. During the Ming Dynasty, key sections of the Great Wall were built with bricks and stones. Local kilns were established to fire bricks and tiles, while stone quarries were opened to produce lime.

Historical records reveal that the labor force for constructing the Great Wall primarily consisted of garrison troops, followed by conscripted laborers, and thirdly, convicts serving sentences through forced labor. During the Qin and Han dynasties, a form of punishment known as “chengdan” involved sentencing individuals to build the Great Wall. They guarded and patrolled during the day and constructed the wall at night, enduring immense hardship. This punishment typically lasted four years.

During the Ming Dynasty’s Great Wall construction, no machinery existed for building or transporting materials. Laborers relied entirely on manual labor to move massive stones weighing over 2,000 jin each and large bricks weighing over 30 jin each. These bricks contained sand and gravel, making them exceptionally hard and nearly impossible to shift. Transport methods primarily involved forming long lines to pass materials along, supplemented by simple tools like handcarts, rolling logs, pry bars, and winches.

Animal labor was occasionally employed as an alternative to human strength. Legend has it that during the construction of Badaling, donkeys carried baskets filled with lime, while bricks were strapped to the horns of goats and driven up the mountain to replace human transport. However, the bulk of the work was still accomplished by human hands. It is no exaggeration to say that the Great Wall embodies the wisdom and blood, sweat, and tears of the Chinese nation over a thousand years.

During the Ming Dynasty’s Great Wall construction, no machinery existed for building or transporting materials. Laborers relied entirely on manual labor to move massive stones weighing over 2,000 jin each and large bricks weighing over 30 jin each. These bricks contained sand and gravel, making them exceptionally hard and nearly impossible to shift. Transport methods primarily involved forming long lines to pass materials along, supplemented by simple tools like handcarts, rolling logs, pry bars, and winches.

Animal labor was occasionally employed as an alternative to human strength. Legend has it that during the construction of Badaling, donkeys carried baskets filled with lime, while bricks were strapped to the horns of goats and driven up the mountain to replace human transport. However, the bulk of the work was still accomplished by human hands. It is no exaggeration to say that the Great Wall embodies the wisdom and blood, sweat, and tears of the Chinese nation over a thousand years.

Cultural Value

The Great Wall is a World Cultural Heritage site of China. It is not only a magnificent defensive structure but also a symbol of the wisdom and diligence of the Chinese nation. As a vital carrier of ancient Chinese civilization, the Great Wall holds extensive cultural value, primarily encompassing the following aspects:

1. Historical Value: The Great Wall stands as a significant witness and remnant of ancient Chinese history. It bears witness to ancient China’s military defenses and cultural exchanges, representing the glorious history and rich cultural heritage of ancient Chinese civilization.

2. Artistic Value: As an outstanding example of ancient Chinese architecture, the Great Wall possesses unique architectural artistry. Its structural components—stone piers, arches, and carvings—exhibit not only aesthetic beauty but also masterful craftsmanship, showcasing the advanced level of ancient Chinese architectural art.

3. Aesthetic Value: As an integral part of Chinese landscape painting, the Great Wall integrates elements of mountains, rivers, architecture, and culture, forming a distinctive landscape-architectural vista of exceptional aesthetic merit.

4. Social Value: The Great Wall serves as a symbol of the Chinese nation and the state, holding profound social significance.

1. Historical Value: The Great Wall stands as a significant witness and remnant of ancient Chinese history. It bears witness to ancient China’s military defenses and cultural exchanges, representing the glorious history and rich cultural heritage of ancient Chinese civilization.

2. Artistic Value: As an outstanding example of ancient Chinese architecture, the Great Wall possesses unique architectural artistry. Its structural components—stone piers, arches, and carvings—exhibit not only aesthetic beauty but also masterful craftsmanship, showcasing the advanced level of ancient Chinese architectural art.

3. Aesthetic Value: As an integral part of Chinese landscape painting, the Great Wall integrates elements of mountains, rivers, architecture, and culture, forming a distinctive landscape-architectural vista of exceptional aesthetic merit.

4. Social Value: The Great Wall serves as a symbol of the Chinese nation and the state, holding profound social significance.

The author believes

It has ignited the Chinese people’s national pride and patriotic fervor, becoming a symbol of the Chinese nation’s cohesion and spirit. As an integral part of Chinese civilization, the Great Wall holds profound cultural significance, carrying vital historical, cultural, and social importance for both the Chinese nation and human civilization as a whole.